Beyond the Dots, Pointillism is Anything but Pointless

Pointillism, a painting technique from the late 19th century, transformed modern art with its innovative use of small, distinct dots of colour.

To fully appreciate the emergence of Pointillism, it is crucial to consider the broader artistic milieu of the late 19th century. The Impressionist movement, which began in the 1870s, had already revolutionised art by focusing on capturing brief moments of light and colour. However, while Impressionism’s loose brushwork and spontaneous style were groundbreaking, they did not satisfy all artists. Some sought a more systematic and scientific approach to painting, one that offered greater precision and structure.

In this environment of artistic exploration, Pointillism began to take form. The technique was significantly influenced by advancements in colour theory, particularly the work of Michel Eugène Chevreul, a French chemist whose research on colour perception profoundly affected the art world. Chevreul’s studies on simultaneous contrast and optical mixing laid the groundwork for Pointillism. His principles gave artists a method to achieve a more precise and scientifically informed representation of light and colour.

The pioneer of Pointillism

Georges Seurat (1859–1891) is widely acknowledged as the pioneer of Pointillism. Seurat’s meticulous approach was deeply rooted in his fascination with colour theory and his desire to develop a more scientific method of painting. His technique involved applying tiny, distinct dots or strokes of pure colour to the canvas. When viewed from a distance, these dots blend optically to create a unified image. This method, known as optical mixing, aimed to produce a more vibrant and luminous effect compared to traditional blending techniques.

Seurat’s magnum opus, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884–1886), is a prime example of his Pointillist technique. This large-scale painting captures Parisians enjoying a leisurely day in a park and is characterised by its precise arrangement of dots and a meticulously constructed composition. The painting’s attention to detail and innovative use of colour illustrate Seurat’s dedication to the principles of Pointillism.

Seurat’s approach was also shaped by his engagement with contemporary scientific theories, including those of Chevreul and physicist Hermann von Helmholtz. These theories provided Seurat with a framework for understanding colour interactions and how they could be harnessed to create visual effects. His work represents a significant departure from the Impressionists’ spontaneous brushwork, showcasing a more systematic and analytical approach to art.

The innovator

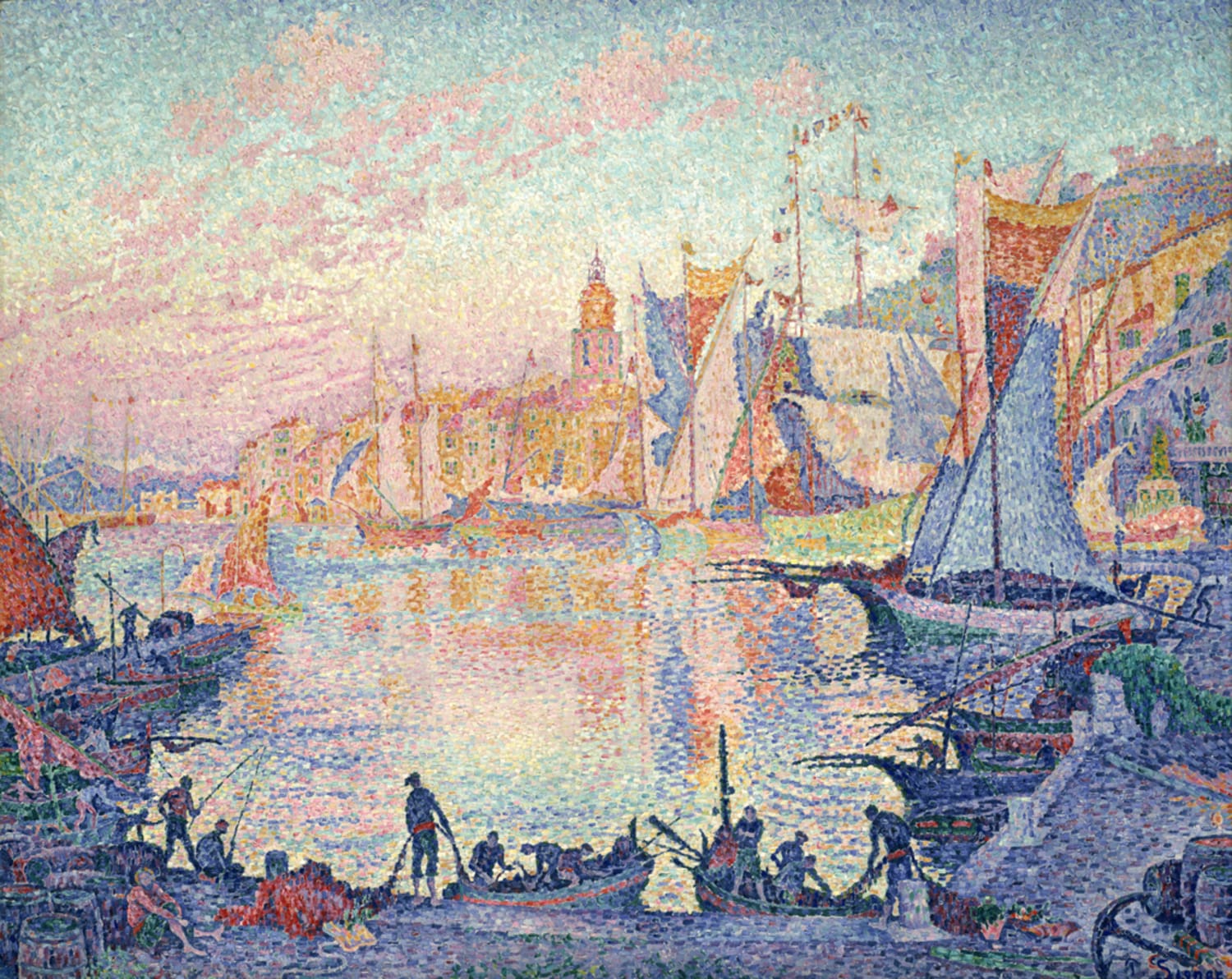

Paul Signac (1863–1935) was another pivotal figure in the development and dissemination of Pointillism. A close collaborator of Seurat, Signac played an essential role in popularising the technique and exploring its possibilities. While Seurat’s work was often noted for its restrained use of colour and form, Signac’s approach was more vibrant and dynamic, reflecting his belief in the expressive power of colour.

Signac’s painting, The Port of Saint-Tropez (1901), exemplifies his Pointillist style. The work captures the lively atmosphere of the Mediterranean port with its bold, bright colours and energetic brushwork. Signac’s application of colour and light demonstrates his commitment to the principles of optical mixing and his conviction in the emotional and expressive potential of Pointillism.

In addition to his artistic contributions, Signac was a fervent advocate for Pointillism. His influential writings, including D'Eugène Delacroix au Néo-Impressionnisme (1899), provided theoretical foundations for the technique and helped to establish its place in the art world. Signac’s efforts were crucial in promoting Pointillism and securing its recognition as a significant movement in modern art.

Theoretical underpinnings of Pointillism

At the heart of Pointillism lies the principle of optical mixing, a process in which separate dots of colour blend in the viewer’s eye to create a cohesive image. This technique relies on the viewer’s perception of colour and light, in contrast to traditional methods that involve physically blending pigments on the canvas.

The scientific basis of Pointillism is closely tied to Michel Eugène Chevreul’s research on colour perception and harmony. Chevreul’s theories, especially his concepts of simultaneous contrast and the effects of light on colour provided a theoretical framework for the Pointillist technique. Simultaneous contrast refers to how the perception of a colour can be altered by the colours surrounding it. For instance, a colour may appear more vibrant or subdued depending on its adjacent hues. This principle is fundamental to Pointillism, as the technique relies on colour interaction to create a sense of vibrancy and depth.

Chevreul’s research also highlighted the importance of optical mixing, where the viewer’s eye blends separate dots of colour to produce a unified image. This method stands in contrast to traditional pigment blending, which can result in a more muted and less dynamic effect.

The influence of Pointillism extends well beyond its initial proponents. The technique has had a profound impact on the evolution of modern art, shaping various movements and artists throughout the 20th century. Its focus on colour theory and optical effects paved the way for new explorations in abstraction and colour field painting.

One of the most significant ways Pointillism influenced modern art was through its emphasis on colour theory. The technique’s exploration of optical mixing and colour perception contributed to the development of innovative approaches to colour in art. For example, the Abstract Expressionist movement, which emerged in the mid-20th century, drew on the principles of colour and light explored by the Pointillists to create bold, dynamic compositions.

Pointillism also left a lasting impression on other creative fields, such as graphic design and printmaking. The technique’s focus on colour and perception has influenced a range of artistic practices and continues to inspire contemporary artists. For instance, the halftone dots used in printmaking, which create the illusion of continuous tone through a pattern of dots, can be seen as a direct descendant of the Pointillist method.

Influence on other artists

Beyond Seurat and Signac, several other artists were either influenced by or contributed to the Pointillist movement:

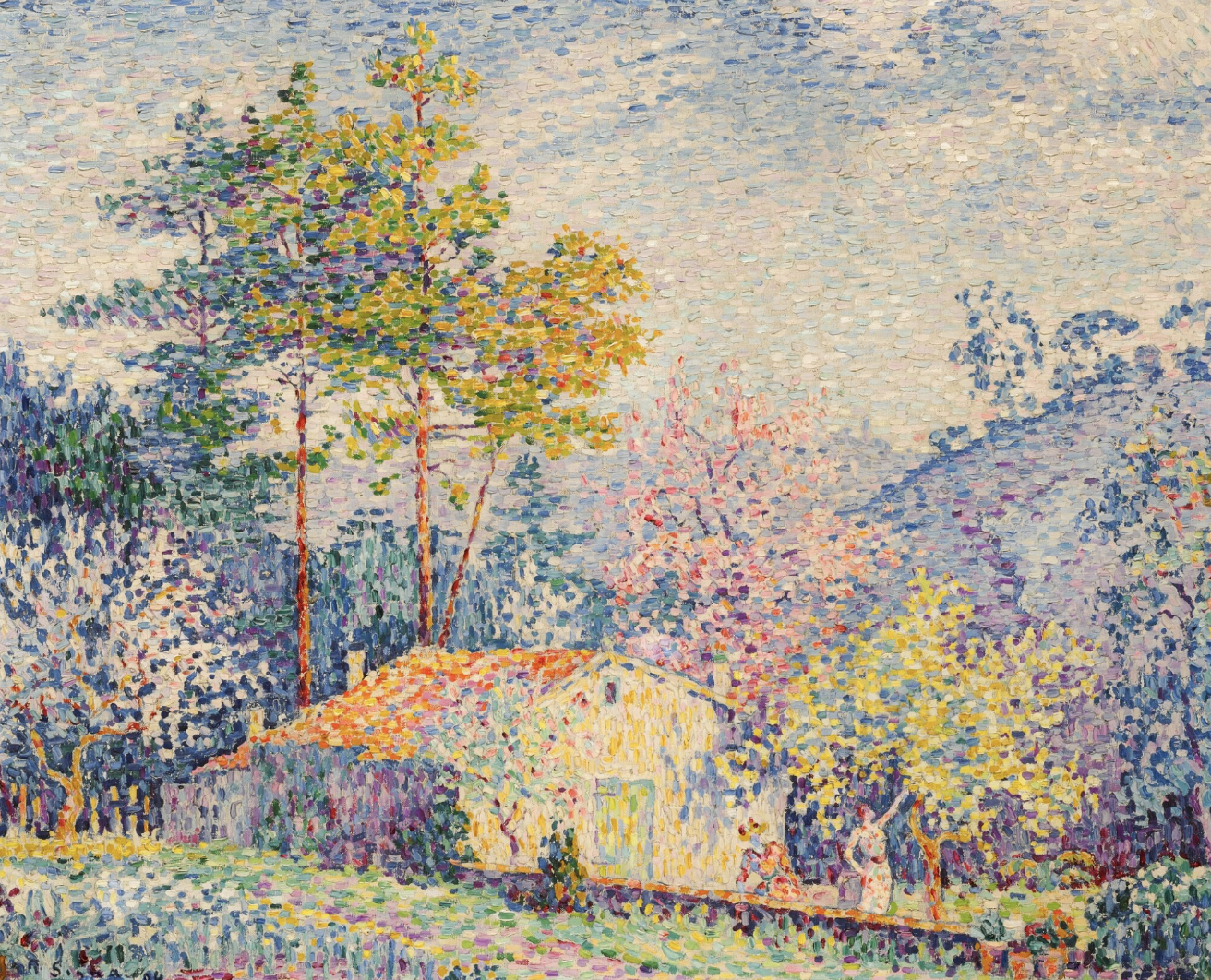

- Henri-Edmond Cross (1856–1910): A French painter who embraced Pointillism and contributed significantly to its development. His works, such as The Evening Air (circa 1893), showcase a vibrant use of colour and light.

- Maximilien Luce (1858–1941): A French painter and printmaker influenced by Pointillism, with notable works like Rue Ravignan (1893).

- Théo van Rysselberghe (1862–1926): A Belgian painter associated with Pointillism. One of his well-known works, The Man at the Helm (1892), illustrates his mastery of light and shadow using the Pointillist technique.

- Charles Angrand (1854–1926): A French Neo-Impressionist artist who was deeply influenced by Pointillism. His painting The Harvesters (1892) exemplifies his subtle use of dots and strokes to evoke atmosphere and natural light.

- Albert Dubois-Pillet (1846–1890): A French army officer and painter who embraced Pointillism early on. His work The Banks of the Marne at Dawn (1888) demonstrates his exploration of colour theory through the Pointillist method.

Influence of Henri Matisse and Vincent van Gogh

Although neither Henri Matisse nor Vincent van Gogh was directly part of the Pointillist movement, both were influenced by its techniques and theories:

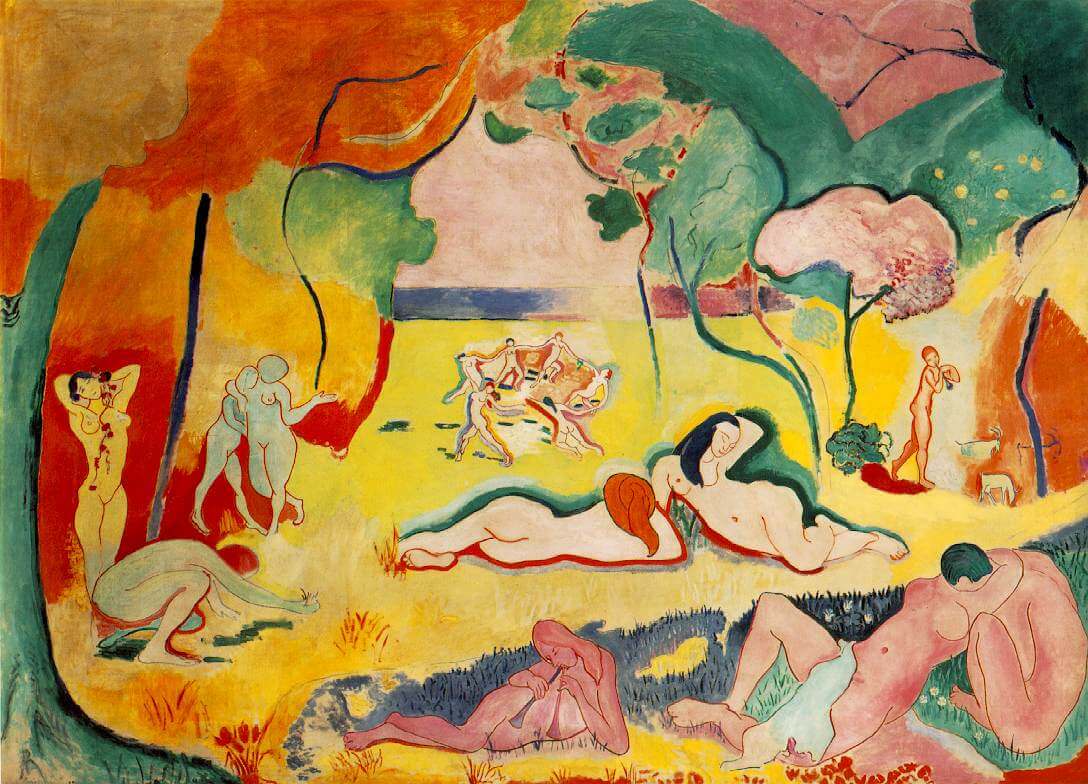

- Henri Matisse (1869–1954): Matisse’s use of colour was indirectly shaped by Pointillist principles. His Fauvist works, such as The Joy of Life (1905), explore vibrant colour and bold compositions, reflecting some of the ideas central to Pointillism.

- Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890): Van Gogh, a contemporary of the Pointillists, engaged with similar ideas about colour and light. Although his style was distinct, with expressive brushstrokes and dynamic forms, his innovative use of colour and light reveals an understanding of principles akin to those of Pointillism. His works, including The Starry Night (1889), demonstrate a deep engagement with the emotional and perceptual effects of colour.

Today, Pointillism is recognised as a significant and influential movement in the history of art. Its emphasis on colour theory, optical effects, and scientific principles ensures its ongoing relevance and interest among contemporary artists and scholars.

Many modern artists have drawn inspiration from Pointillism, experimenting with digital technology to create new forms of Pointillist art. This includes exploring how pixels and digital dots can replicate the effects of traditional painting. Others have integrated Pointillist techniques into mixed-media works, combining them with other artistic methods to produce innovative and contemporary pieces.

Pointillism stands as a testament to the transformative power of artistic innovation. By challenging conventional techniques and embracing a scientific approach to colour and light, Pointillism has left an indelible mark on the history of art, continuing to inspire and captivate audiences and artists