Abstract Expressionism Wasn’t Just Chaotic Splatters on Canvas. It Was a Visceral, Emotional Revolution

Abstract Expressionism was more than chaotic splatters; it was a revolutionary movement that captured raw emotion and existential angst, challenging artistic norms and reflecting the turbulent human experience.

In the mid-20th century, a seismic shift reverberated through the world of art. Abstract Expressionism emerged in post-war America, challenging the conventions of representational art and the boundaries of artistic expression. While often reduced to a simplistic notion of ‘splatters on canvas,’ this movement was anything but arbitrary. It was, in fact, a profound and revolutionary break with tradition, marked by its intellectual depth, its raw emotional intensity, and its philosophical underpinnings.

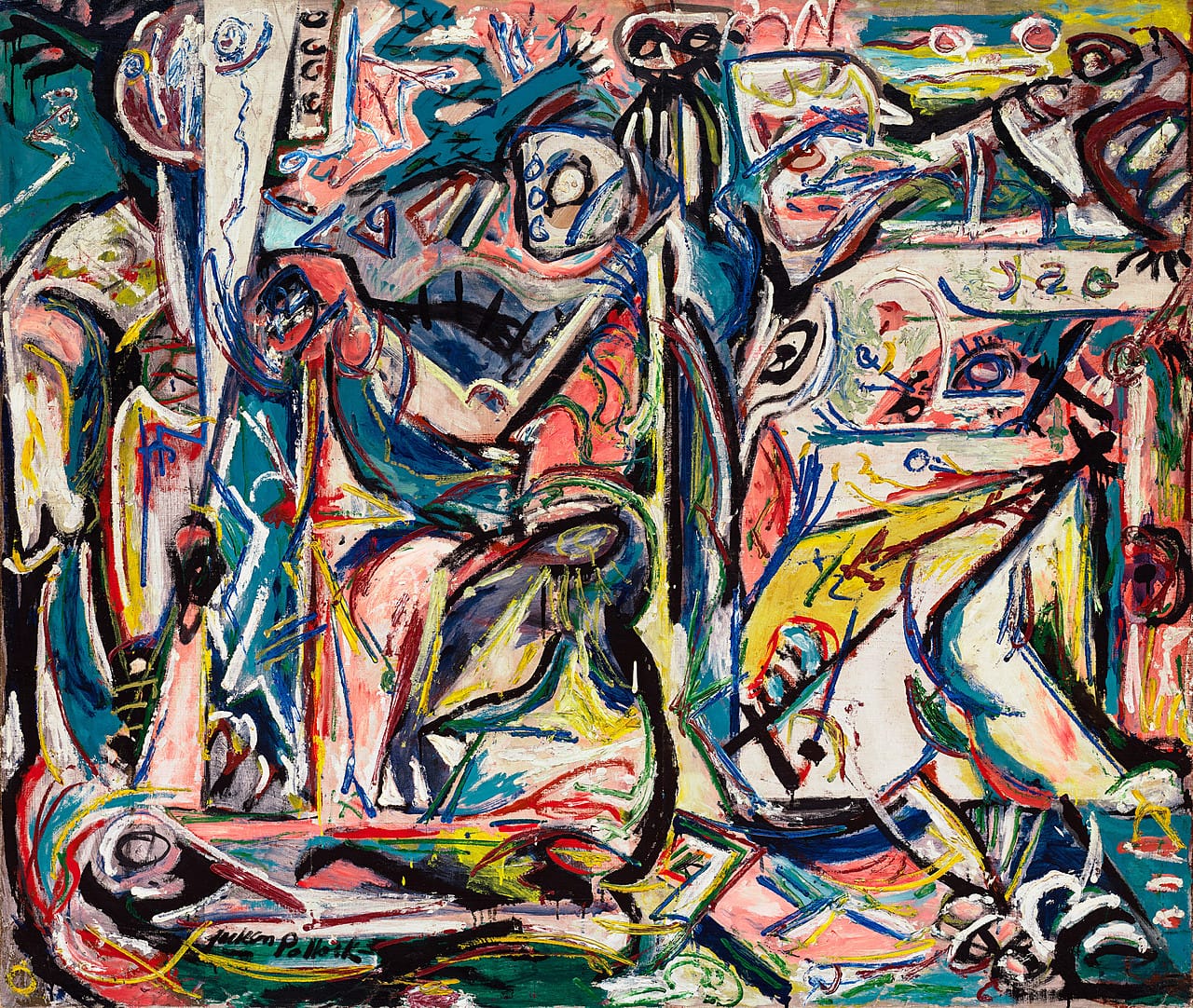

At the heart of Abstract Expressionism lay a fierce commitment to the individual’s inner world—the subconscious, the emotional, and the instinctive. In contrast to the structured, figurative forms that had dominated much of Western art history, Abstract Expressionists sought to communicate their internal landscapes without mediation.

These artists—Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, and others—sought to move beyond the constraints of realism and to convey the intensity of human existence in its most unfiltered, elemental form.

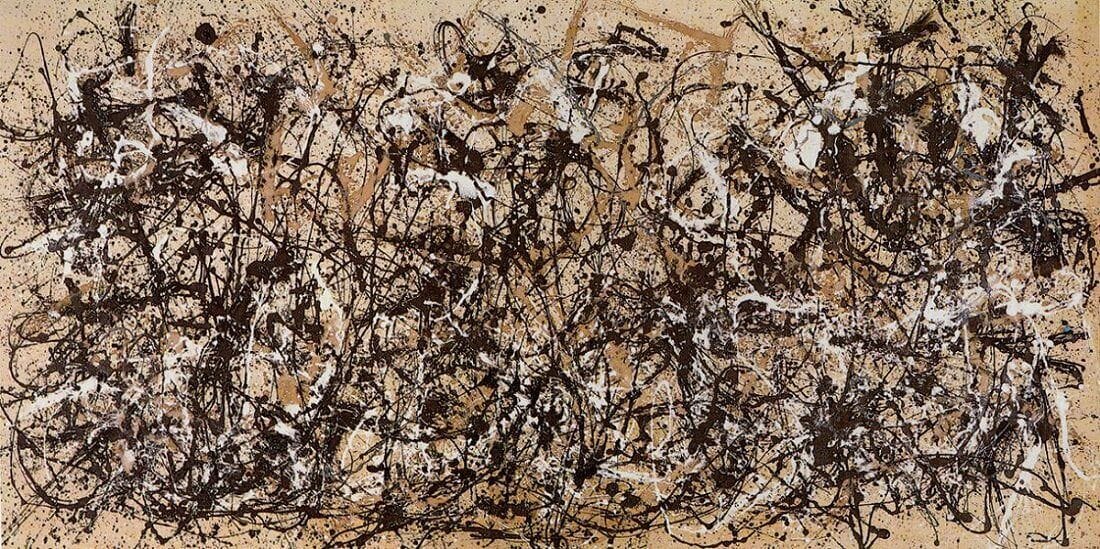

The notion that Abstract Expressionism is mere chaos reveals a misunderstanding of both its techniques and its intentions. Consider Jackson Pollock’s "drip paintings", which are perhaps the most recognisable symbols of the movement. The seemingly random flicks and streaks of paint may appear haphazard, yet Pollock’s method was intensely deliberate.

His canvases were laid flat on the floor, where he could interact with the surface from all angles. Paint was poured, dripped, and thrown, not to evoke random patterns, but to capture the artist’s physical movement in relation to the canvas.

Pollock’s "action painting" reflected a fundamental shift in how art was made: the process itself became part of the meaning. His gestures weren’t just marks on a surface—they were a visual manifestation of his emotions, his psyche, and his body in motion.

The work was as much a record of the artist’s internal state as it was an aesthetic object. This approach was radical. In a world reeling from the trauma of two world wars and the horrors of the Holocaust, Pollock’s violent, unpredictable strokes reflected a new kind of truth, one that rejected the rational order of the past in favour of emotional immediacy.

The emotional core of Abstract Expressionism extended beyond Pollock’s kinetic approach. Mark Rothko, another towering figure in the movement, took an almost opposite route, yet arrived at a similar emotional destination.

His work is characterised by large blocks of colour, seemingly simple in form but laden with emotional weight. Rothko’s canvases pulse with a sense of spirituality, inviting the viewer to stand before them in contemplation. The expanses of colour—deep reds, purples, blacks—envelop the viewer, evoking an existential experience.

Rothko’s art was not about the mere aesthetic pleasure of colour, nor was it entirely abstract. He was deeply invested in human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, and the sublime. His goal was to produce a sense of awe and introspection in the viewer, to offer an experience that transcended the physical world. In this way, Rothko’s work echoes the Romantic artists of the 19th century, who sought to capture the ineffable emotions of the human soul. But unlike the Romantics, Rothko stripped away narrative, representation, and detail to focus solely on colour, form, and the power of the unspoken.

What united the Abstract Expressionists was their rejection of convention and their embrace of emotional depth. They refused to be bound by the formal structures that had long defined art in Europe. For them, art was no longer about creating a window into the world; it was about creating an experience, a confrontation with the raw and unmediated emotions of the human condition. In a way, the chaos often attributed to Abstract Expressionism reflected the chaos of the post-war world. But beneath that surface disorder lay profound questions about existence, identity, and meaning.

Willem de Kooning, another central figure, blurred the line between abstraction and figuration. His works, especially those of his "Woman" series, are tempestuous and full of contradictions. Here, abstraction becomes intertwined with representation, as fragmented, distorted forms suggest the presence of the human figure without fully rendering it. De Kooning’s aggressive brushstrokes and slashing forms speak to an underlying tension: the struggle between creation and destruction, order and chaos, control and abandon.

The Abstract Expressionists’ rebellion was not just a rejection of artistic convention; it was also a political and philosophical statement. In the wake of World War II, the moral and intellectual frameworks that had previously governed Western thought were in disarray. The horrors of the war had revealed the fragility of civilisation, and the certainty of progress was shattered. For many, including the Abstract Expressionists, the world no longer made sense in traditional terms. The old ways of thinking—rationalism, order, and structure—seemed inadequate in the face of such immense devastation.

The movement’s origins in America were also significant. For centuries, the artistic centre of the world had been Europe, and American art had largely followed European trends. Abstract Expressionism represented a shift in this dynamic. For the first time, New York replaced Paris as the global capital of the art world.

In a sense, Abstract Expressionism was America’s declaration of artistic independence, a signal that American artists were no longer bound by European traditions. They were forging a new path, one that reflected the existential anxieties of the 20th century but also embraced the freedom and innovation of the New World.

This new path was not universally embraced, of course. To its critics, Abstract Expressionism appeared self-indulgent, inaccessible, or devoid of meaning. The works could appear so removed from reality that viewers often found themselves disoriented, unsure of how to engage with them. This very reaction, however, underscores the movement’s power. Abstract Expressionism was not about providing easy answers or reassuring the viewer with familiar images. Instead, it asked viewers to confront the unknown, to experience art in a new way—viscerally, physically, and emotionally.

In the end, Abstract Expressionism was far more than splatters on canvas or arbitrary smears of paint. It was a profound exploration of the human condition, a response to the disorienting realities of modern life, and a search for meaning in a world that often seemed incomprehensible. It broke with the past, not out of a desire for novelty but because the past’s certainties no longer seemed valid. Through their unconventional techniques and their unflinching focus on emotion, the Abstract Expressionists transformed the landscape of modern art and invited viewers to see not just with their eyes, but with their hearts.

What remains from this movement is not merely a collection of bold gestures or splashes of paint, but a legacy of emotional and intellectual engagement that continues to resonate in today’s fractured world. The movement reminds us that art is not always meant to explain or represent the external world; sometimes, it exists to mirror the tumultuous, ungraspable currents within us all.